95

When visitors arrive at the Florence Nightingale Museum they quickly identify themselves as a part of Florence Nightingale’s legacy. This is how we can state with such confidence that our visitors are 95% nurse. An impressive figure that does exclude schools, pre-booked groups and national promotions.

One of the most contentious issues facing the Museum is the need for an admission charge. Not surprisingly nurses and many other visitors are disappointed that the exhibition is not funded nationally as recognition of the nursing profession. It is an understandable misunderstanding we have to accept as a side effect of being a focal point. Nurses are highly skilled individuals with a pronounced sense of historical and communal pride; protecting that sense of individual and collective worth is after all a key objective for the Museum.

12

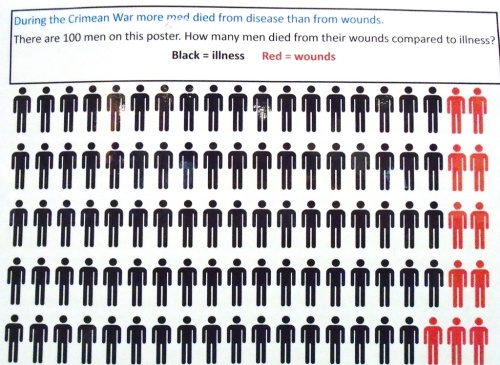

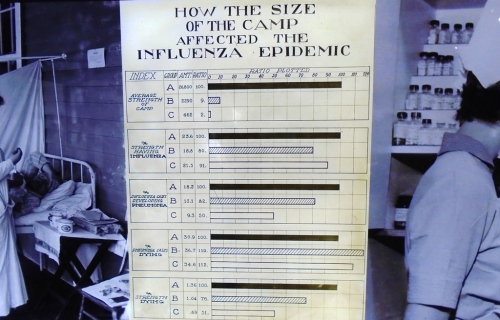

We exist outside the vocabulary expected of a medical museum and instead of grisly instruments we offer grisly statistics illustrating the mortality rates of ordinary people denied basic health care. Florence Nightingale began the process that ultimately established the popular culture symbols of the nursing profession. The Museum relates Nightingale’s life and work through relatively humble objects that perfectly illustrate how much was achieved with little more than soap and a fierce intellect. The therapeutic nature of the exhibition will be boosted by the return of ten Victor Tardieu paintings, depicting a First World War field hospital. True to form, they are a remarkably upbeat series of pictures.

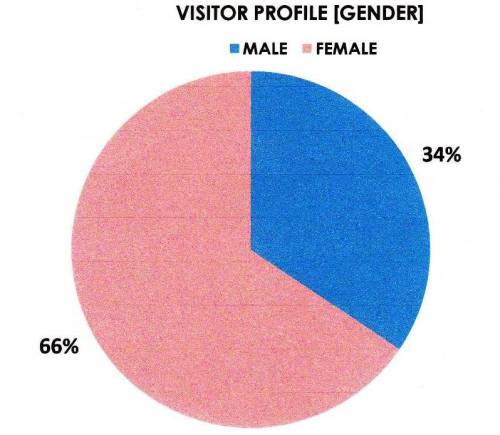

For the last few years the Front of House team have been recording statistical information profiling visitors to the Museum. It is an ongoing activity which could prove very interesting in the coming months as a refreshed website and exhibition revamp are completed. The process of recording this very useful information has become second nature to the team and has, over time, become a soothing daily activity.

16

The next major project for the Museum will be unveiled on 12th May, the anniversary of Florence Nightingale’s birthday. “Take me to Neverland” will explore the history of J M Barrie’s Peter Pan, featuring items from the collection of Great Ormond Street Hospital. The forthcoming exhibition has already created a notable buzz amongst our visitors, especially families. A range of events planned for 2016 builds on last year’s eclectic Twistmas festival. They begin with February’s half-term maths theme, evening talks and more planned weekend activities boosting access to a collection which is 100% relevant to everybody.